The global financial crisis, which began in 2008 and whose repercussions will continue to echo round the world for years to come, has triggered myriad criticisms of the modern capitalist system: it is too ‘speculative’

Value has gone from being a category at the core of economic theory, tied to the dynamics of production (the division of labour, changing costs of production), to a subjective category tied to the ‘preferences’ of economic agents. Many ills, such as stagnant real wages, are interpreted in terms of the ‘choices’ that particular agents in the system make, for example unemployment is seen as related to the choice that workers make between working and leisure.

by

Mariana Mazzucato*

It rewards ‘rent-seekers’ over true ‘wealth creators’ and it has permitted the rampant growth of finance, allowing speculative exchanges of financial assets to be compensated more than investments that lead to new physical assets and job creation.

Debates about unsustainable growth have become louder, with concerns not only about the rate of growth but also its direction. Recipes for serious reforms of this ‘dysfunctional’ system include making the financial sector more focused on long-run investments; changing the governance structures of corporations so they are less focussed on their share prices and quarterly returns; taxing quick speculative trades more heavily; legally and curbing the excesses of executive pay.

In my latest book, The Value of Everything, I have argued that such critiques are important but will remain powerless – in their ability to bring about real reform of the economic system – until they become firmly grounded in a discussion about the processes by which economic value is created. It is not enough to argue for less value extraction and more value creation. First, ‘value’, a term that once lay at the heart of economic thinking, must be revived and better understood.

Value has gone from being a category at the core of economic theory, tied to the dynamics of production (the division of labour, changing costs of production), to a subjective category tied to the ‘preferences’ of economic agents. Many ills, such as stagnant real wages, are interpreted in terms of the ‘choices’ that particular agents in the system make, for example unemployment is seen as related to the choice that workers make between working and leisure.

And entrepreneurship – the praised motor of capitalism – is seen as a result of such individualized choices rather than of the productive system surrounding entrepreneurs – or, to put it another way, the fruit of a collective effort. At the same time, price has become the indicator of value: as long as a good is bought and sold in the market, it must have value. So rather than a theory of value determining price, it is the theory of price that determines value.

Along with this fundamental shift in the idea of value, a different narrative has taken hold. Focused on wealth creators, risk taking and entrepreneurship, this narrative has seeped into political and public discourse. It is now so rampant that even ‘progressives’ critiquing the system sometimes unintentionally espouse it. When the UK Labour Party lost the 2015 election, leaders of the party claimed they had lost because they had not embraced the ‘wealth creators’. And who did they think the wealth creators were? Businesses and the entrepreneurs leading them. Feeding the idea that value is created in the private sector and redistributed by the public sector. But how can a party that has the word ‘labour’ in its title not see workers and the state as equally vital parts of the wealth creation process?

Such assumptions about the generation of wealth have become entrenched, and have gone unchallenged. As a result, those who claim to be wealth creators have monopolised the attention of governments with the now well-worn mantra of: give us less tax, less regulation, less state and more market. By losing our ability to recognize the difference between value creation and value extraction, we have made it easier for some to call themselves value creators and in the process extract value. Understanding how the stories about value creation are around us everywhere – even though the category itself is not – is essential for the future viability of capitalism.

To offer real change we must go beyond fixing isolated problems, and develop a framework that allows us to shape a new type of economy: one that will work for the common good. The change has to be profound. It is not enough to redefine GDP to encompass quality-of-life indicators, including measures of happiness, the imputed value of unpaid ‘caring’ labour and free information, education and communication via the Internet.

It is also not enough to tax wealth. While such measures are important in themselves, they do not address the greatest challenge: defining and measuring the collective contribution to wealth creation, so that value extraction is less able to pass for value creation. As we have seen, the idea that price determines value and that markets are best at determining prices has all sorts of nefarious consequences. To sum up, four stand out.

First, this narrative emboldens value extractors in finance and other sectors of the economy. Here, the crucial questions – which kinds of activities add value to the economy and which simply extract value for the sellers – are never asked. In the current way of thinking, financial trading, rapacious lending, funding property price bubbles are all value-added by definition, because price determines value: if there is a deal to be done, then there is value. By the same token, if a pharma company can sell a drug at a hundred or a thousand times more than it costs to produce, there is no problem: the market has determined the value.

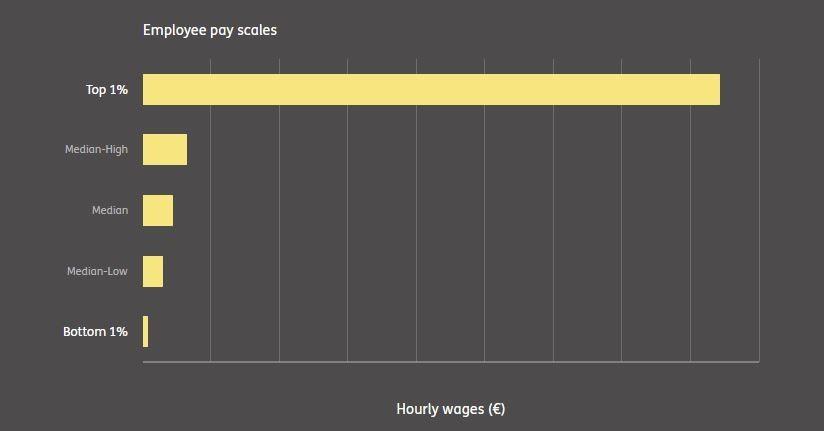

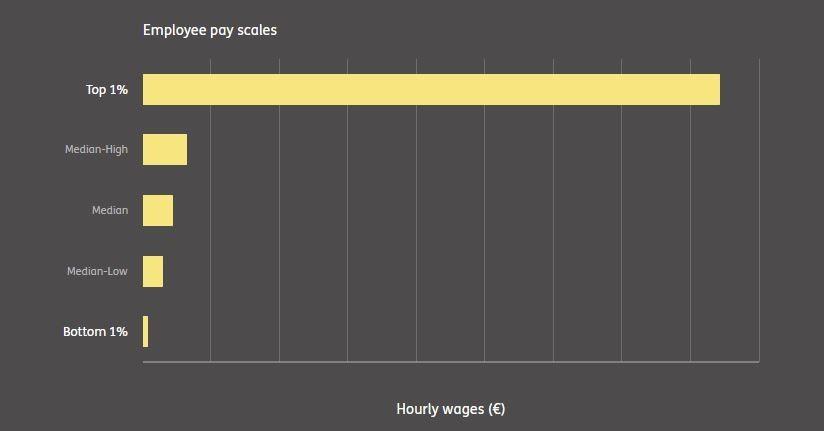

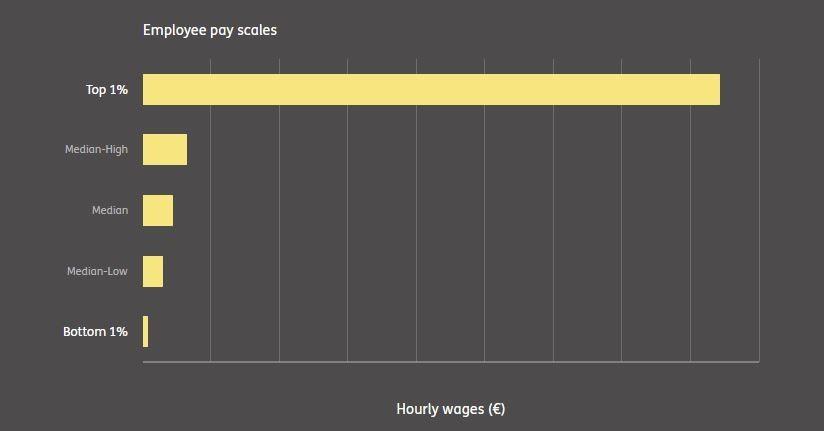

The same goes for chief executives who earn 340 times more than the average worker (the actual ratio in 2015 for companies in the S&P 500). The market has decided the value of their services – there is nothing more to be said. Economists are aware that some markets are not fair, for example when Google has something close to a monopoly on search advertising; but they are too often enthralled by the narrative of market efficiency to worry whether the gains are actually justly earned profits, or merely rents. Indeed, the distinction between profits and rents is not made.

Price-equals-value thinking encourages companies to put financial markets and shareholders first, and to offer as little as possible to other stakeholders. This ignores the reality of value creation – as collective processes. In truth, everything concerning a company’s business – especially the underlying innovation and technological development – is intimately interwoven with decisions made by elected governments, investments made by schools, universities, public agencies and even movements by not-for-profit institutions. Corporate leaders are not telling the whole truth when they say that shareholders are the only real risk takers and hence deserve the lion’s share of the gains from doing business.

Second, the conventional discourse devalues and frightens actual and would-be value creators outside the private business sector. It’s not easy to feel good about yourself when you are constantly being told you’re rubbish and/or part of the problem. That’s often the situation for people working in the public sector, whether these be nurses, civil servants or teachers. The static metrics used to measure the contribution of the public sector, and the influence of Public Choice theory on making governments more ‘efficient’, has convinced many civil-sector workers they are second-best. It’s enough to depress any bureaucrat and induce him or her to get up, leave and join the private sector, where there is often more money to be made.

So public actors are forced to emulate private ones, with their almost exclusive interest in projects with fast paybacks. After all, price determines value. You, the civil servant, won’t dare to propose that your agency could take charge, bring a helpful long-term perspective to a problem, consider all sides of an issue (not just profitability), spend the necessary funds (borrow if required) and – whisper it softly – add public value. You leave the big ideas to the private sector which you are told to simply ‘facilitate’ and enable.

And when Apple or whichever private company makes billions of dollars for shareholders and many millions for top executives, you probably won’t think that these gains actually come largely from leveraging the work done by others – whether these be government agencies, not-for-profit institutions, or achievements fought for by civil society organizations including trade unions that have been critical for fighting for workers’ training programmes.

Third, this market story confuses policymakers. By and large, policymakers of all stripes want to help their communities and their country, and they think the way to do so is to put more trust in market mechanisms. Step back and let the market magic work: this has become the slogan of centre-left politicians from California to Austria to Australia. The crucial thing is to be seen to be business-friendly. As a result, politicians and all too many government employees are like putty in the hands of those who claim to be value creators.

Regulators end up being lobbied by businesses and induced to endorse policies which make incumbents even richer. Examples include ways in which governments across much of the Western world have been persuaded to reduce capital gains tax, even though there is no reason to do so if the aim is to promote long-term investments rather than short-term ones.

And lobbyists with their innovation stories have pushed through the Patent Box policy, which reduces tax on the profits generated from 20-year patent-based monopolies – even though the policy’s main impact has been merely to reduce government revenue, rather than increasing the types of investments that led to the patents in the first place.

All of which serves only to subtract value from the economy and make for a less attractive future for almost everyone. Not having a clear view of the collective value creation process, the public sector is thus ‘captured’ – entranced by stories about wealth creation which have led to regressive tax policies that increase inequality.

Fourth, and last, the confusion between profits and rents appears in the ways we measure growth itself: GDP. Indeed, it is here that the production boundary comes back to haunt us: if anything that fetches a price is value, then the way national accounting is done won’t be able to distinguish value creation from value extraction, and thus policies aimed at the former might simply lead to the latter.

This is not only true for the environment where picking up the mess of pollution will definitely increase GDP (due to the cleaning services paid for) while a cleaner environment won’t necessarily (indeed if it leads to less ‘things’ produced it could decrease GDP), but also as we saw to the world of finance where the distinction between financial services that feed industry’s need for long-term credit versus those financial services that simply feed other parts of the financial sector are not distinguished.

Only with a clear debate about value can rent-extracting activities in every sector, including the public one, be better identified and deprived of political and ideological strength.

This is an extract from Mariana Mazuccato's latest book, The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy, published by Allen Lane.

*Professor in the Economics of Innovation and Public Value, University College London (UCL)