by George A. Zairis*

During the first quarter our century, the European Union faced exceptionally turbulent times regarding the government debt levels. A sequence of major ‘‘shocks’’ reshaped fiscal positions across member states, forcing policymakers to confront structural vulnerabilities in the architecture of the Economic and Monetary Union. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2009, the subsequent Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic stand out as the three major events of this period. Together, they form the core pillars of a challenging chapter in Europe’s economic history - one that future historians will certainly examine as a turning and crucial point for debt dynamics in the EU area.

At this stage, it is worth ‘‘pausing’’ to define the very concept of “debt” - a word that politicians, journalists, and economists routinely deploy in their narratives, though not always 100% understand the exact meaning. According to Eurostat, the general government gross debt, also known as Maastricht debt or public debt, is ‘‘the nominal (face) value of total gross debt outstanding at the end of the year or quarter and consolidated between and within the government subsectors. General government gross debt comprises outstanding stocks of liabilities in the financial instruments’ currency and deposits, debt securities and loans at the end of the reference period’’.

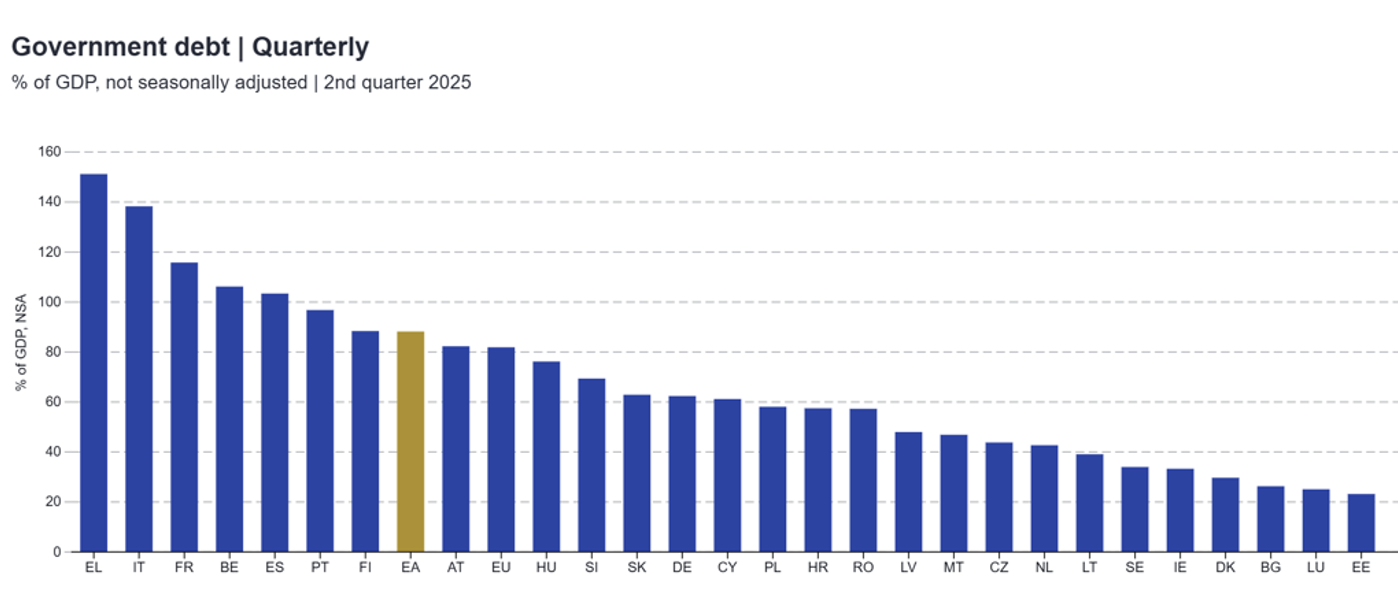

As of the latest published results (Q2 2025), the euro area’s general government gross debt-to-GDP ratio reached 88.2%, up from 87.7% in the previous quarter. A similar movement was observed across the EU, where the ratio rose from 81.5% to 81.9%, indicating a continued, albeit modest, increase in sovereign debt levels.

Comparing government debt levels (% of GDP) across EU member states remains a complex exercise. Countries such as Greece (151.2%) and Italy (138.3%) continue to display some of the highest debt ratios in the Union, whereas Luxembourg (25.1%) and Estonia (23.1%) sit at the opposite end of the spectrum with significantly lower levels. This disparity illustrates both the diversity and the resilience of the EU architecture. It is equally important to remember that debt is only one among many indicators monitored by EU economists and policymakers when assessing fiscal stability. As a reference point, the latest published Eurostat figures for Q2 2025 provide a clear snapshot of government debt as a percentage of GDP across the Union.

Source: Eurostat

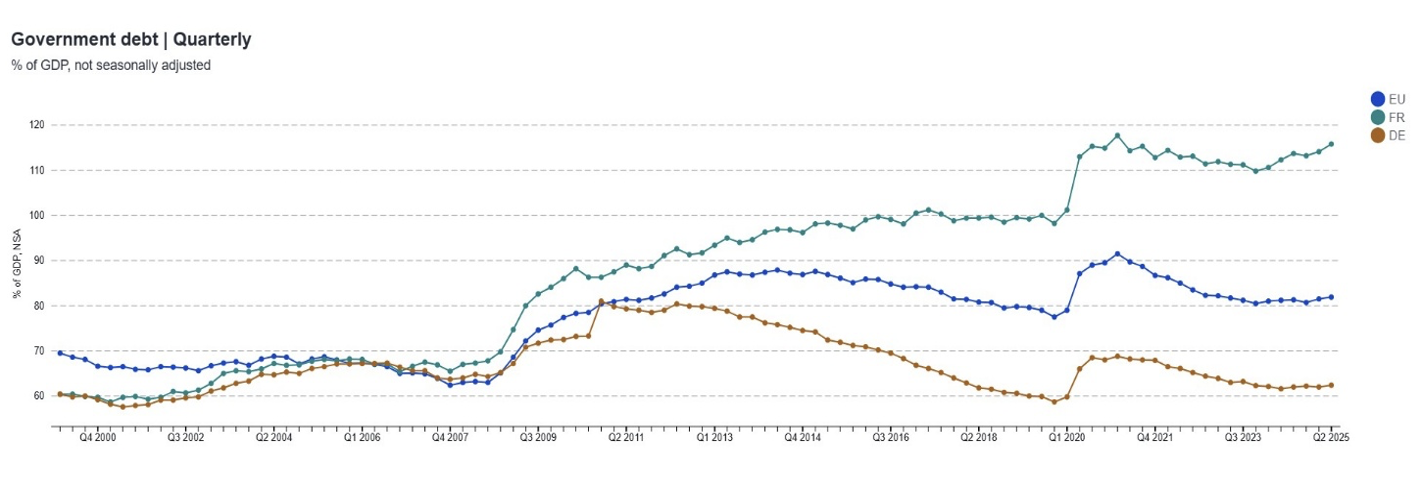

In recent years, the old narrative of a fiscally fragile Southern Europe versus a fiscally robust Northern Europe is losing ground as even the large Northern economies are now under strain. For instance, France, long considered a core European pillar, now posts a government debt-to-GDP ratio above 115 % accompanied by recurring political instability that places its governing coalitions under frequent pressure. Similarly, Germany, historically among the most fiscally prudent euro-area economies, is projected to see its debt burden rise sharply over the coming years

Source: Eurostat

Ultimately, the debate on public debt in the EU is no longer about identifying a single group of “problem countries,” but about understanding systemic fiscal risk in an ageing, slower-growing economic alliance. Even Germany - long perceived as Europe’s fiscal anchor - is now facing structural pressures driven by demographic change, rising defense and climate-transition spending, and a more constrained growth outlook.

This transition shows a broader reality which is the fact that the debt sustainability in the EU will depend less on rigid labels or historical stereotypes and more on credible fiscal frameworks, productivity-enhancing reforms, and political capacity to prioritize long-term stability over short-term expediency. In that sense, decoding debt is not merely an exercise in numbers, but a test of Europe’s economic governance for the decades ahead!

*Senior Manager with specialization in advisory services to EU & Public Institutions. He holds a master’s degree in Banking Innovation and Risk Analytics from the University of Edinburgh and a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Athens. Currently, he is also pursuing a PhD in Sustainable Metrics

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer